Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 16

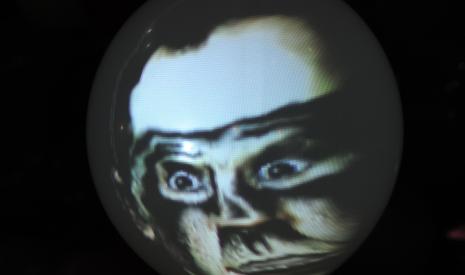

Ghosts and spectres (1/3)

“Hell is empty, and all the devils are here”

The Tempest, William Shakespeare

In Shakespearean times, spectres, demons and spirits were the subject of debates held in the highest spheres of society. James I, who succeeded to Queen Elizabeth, authored a treatise on demonology just after Hamlet was written. The question then was not whether or not these beings were real, but rather how writers could define their diverse and naturally unstable nature. How could they be identified? How could we differentiate them from one another? Are spectres always also demons, or are they the incarnation of a soul lost in Purgatory? Answers to these questions varied widely whether one was a Catholic or a Protestant.

We see how Shakespeare, undeniably a man of his time, was familiar with these questions. His audience at the time was probably not surprised to see ghosts appear in his plays. However, because they believed in ghosts, they would have probably been terrified. The frightening normality of ghosts spectacularly enriched the connection between the world of the living and the world of the dead, adding an in-between realm: the world of those who are “neither living nor dead” but still definitely here. After all, in Shakespeare’s work, killing isn’t enough: one also needs to get rid of the dead person’s soul. This is obviously an impossible task, even for his vilest and most twisted character. Richard III has first-hand experience of this: before dying on the battlefield he endured a night of terror, visited by all the people he had murdered.

What is interesting in Shakespare’s work is that, every time, ghosts appear in troubled times, in periods of deep changes or when a character, crumbling under the weight of events, is close to slipping into madness. There are no happy spectres, no bogus ghosts. Apparitions are always dramatic – deadly even – for the character who is unlucky enough to meet them. Hamlet is, without a doubt, the most famous example. When he appears, his father’s ghost makes it lethally impossible to obey the fatherly orders.

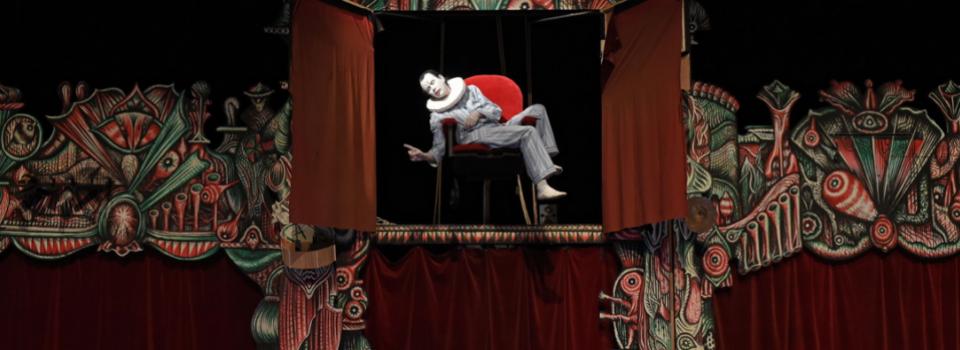

The dead and the living are intertwined in Shakespeare’s theatre, in the same way comedy and tragedy, dialogues and monologues, rawness and sacredness, violence and tenderness are. The dead and the living exist with the same degree of reality, creating an uncanny, unsettling mystery that can only be shown through the art of theatre.

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 01

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 02

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 03

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 13

- Carnet de bord # 16 Richard III – Loyaulté me lie

- Carnet de bord # 17 Richard III – Loyaulté me lie

- Carnet de bord # 18 Richard III – Loyaulté me lie

- Carnet de bord # 19 Richard III – Loyaulté me lie

- Carnet de bord # 20 Richard III – Loyaulté me lie

- Carnet de bord # 21 Richard III – Loyaulté me lie

- Carnet de bord # 22 Richard III – Loyaulté me lie

- Carnet de bord # 23 Richard III – Loyaulté me lie

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 04

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 05

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 06

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 07

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 08

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 09

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 10

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 11

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 12

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 14

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 15

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 16

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 17

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 18

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 19

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 20

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 21

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 22

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 23

- Richard III – Loyaulté me lie # 24